Season 1, Episode 48

Joan orders the city of Lleida to pay what they owe to a creditor.

Episode 48

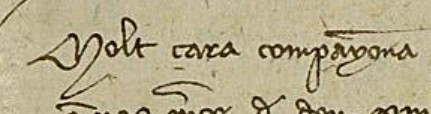

](/historians-notebook-s1-episodes/images/feb-10-aca-cr-r1825-f32r-joan.jpg)

ACA CR R1825 f32r Source: PARES

Today’s Document

- Subject: Joan orders the Lleida town council to pay Berenguer de Almencario

- Date: February 10, 1387

- Day of the Week: Sunday

- Language: Latin

- Archival Reference Number: ACA CR R1825 f32r

- Link to PARES

- Place: Barcelona

- Sender: Joan

- Recipients: officials in charge of Lleida’s finances

Historical Thinking Notes

-

Sourcing: Joan, as the highest ranking political official in the land, would likely sway the town council to pay Berenguer de Almencario; however, it is possible that the identity or reputation of de Almencario played a role in Lleida’s refusal to pay him thus far - perhaps Lleida considers his terms unjust

-

Contextualization: this document reveals much about the high financialization of the Crown of Aragon in the late fourteenth century; there were a dizzying array of loan instruments, some constructed for elites, some for corporate bodies like cities, and others for peasants; furthermore, by the late 1380s, the banking crises set off by Pere the Ceremonious’s financial decisions at the start of the decade had created ‘constant financial emergencies’1; see Additional Note below for further economic context

-

Corroboration: the document examined in Episode 46 is also about Lleida but at this time I cannot tell if there is any connection between that and today’s document; based on my understanding of the widespread occurrence of the censal loans, I am pretty sure that this will not be the last time that I see a document in which Joan must weigh in on the problems a municipality has with paying back a creditor

-

Close-Reading: it is possible that the reference to ‘reprisalarium’ is made to forbid violent reprisals, as ChatGPT suggests, but I am doubtful that violence was involved in this case because it was a municipal debt and my impression is that violence would normally come from individuals in a dispute or families in feuds

What is this document doing?

- This document asserts the king’s role as a decider in high-value financial disputes.

- The document reveals the force behind the censal system, in terms of the potential for reprisals and further monetary penalties.

Questions

- Did Lleida have the money to pay Berenguer de Almencario?

- Were the initial terms of the censal fair to the city of Lleida?

- Had Berenguer de Almencario complained to Pere the Ceremonious in the last year or was this situation new at this time?

- Was this financial situation related to the longer document about Lleida from two days before?

- What previous financial arrangements did Berenguer de Almencario arrange and was he in financial trouble due to the lack of repayment from Lleida?

- Did Joan or the state treasury benefit from any financial deals with Berenguer de Almencario?

Additional Note about Financial Crises from 1380-1396

A 2016 article by Gaspar Feliu i Montfort presents an economic analysis with important implications for understanding the financial aspects of the reign of Joan and Violant.2 The economic context of the Catalan financial industry of the fourteenth century provides overwhelming evidence for the interpretation that by the time of Joan’s ascension to the throne there was nothing any monarch could have done to achieve control over the finances of the state. It is reasonable to credit Joan with an understanding of the situation, since he witnessed his father’s navigation of the 1380 failure of the banking firm of des Cuas and d’Olivella. This firm, the monarchy’s primary source of cash on credit, was a creditor for loans to Pere and Joan that totaled over 314,000 lliures. Pere simply stopped paying, initiating the firm’s bankruptcy, but then the king provided the bankers with a moratorium, in effect helping them to escape their own creditors. The lesson Joan very well might have taken from this saga: there is no discernible financial reality and the financial system was merely a game of musical chairs.

AI Usage

I relied quite heavily on ChatGPT to help with the Latin translation of this document. ChatGPT also reminded me of the article by Sánchez, Sesma Muñoz, and Furió, which was very helpful in understanding the economic context to this document.

Bibliography

- Feliu i Montfort, Gaspar. “Finances, Currency and Taxation in the 14th and 15th Centuries.” Catalan Historical Review, no. 9 (2016): 25–44.

- Girona y Llagostera, Daniel. “Itinerari de l’Infant En Joan, Fill Del Rei En Pere III. 1350-1387.” III Congreso de Historia de La Corona de Aragón (Valencia), Hijo de F. Vives Mora, 1923, 169–592. Available on Google Books, accessed December 26, 2025.

- Salleras Clarió, Joaquín. “La Baronía de Fraga: Su Progresiva Vinculación a Aragón (1387-1458).” Universitat de Barcelona, 2006.

- Sánchez, Manuel, Ángel Sesma Muñoz, and Antoni Furió. “Old and New Forms of Taxation in the Crown of Aragon (13th-14th Centuries).” In La fiscalità nell’economia Europea secc. XIII-XVIII, edited by Simonetta Cavaciocchi. Firenze University Press, 2008. Available for free at CSIC

- Tello Hernández, Esther. “Auditing of Accounts as an Instrument of Royal Power in Catalonia (1318-1419).” In Accounts and Accountability in Late Medieval Europe: Records, Procedures, and Socio-Political Impact. Brepols, 2020.

-

Manuel Manuel, Ángel Sesma Muñoz, and Antoni Furió, “Old and New Forms of Taxation in the Crown of Aragon (13th-14th Centuries).” In La fiscalità nell’economia Europea secc. XIII-XVIII, edited by Simonetta Cavaciocchi, (Firenze University Press, 2008), 8. ↩

-

Gaspar Feliu i Montfort, “Finances, Currency and Taxation in the 14th and 15th Centuries,” Catalan Historical Review, no. 9 (2016): 25–44, at 30-36. ↩