Season 1 FAQs

Why is motto of The Historian’s Notebook ‘dissatisfaction guaranteed’?

If you read anything historical and in the end you feel satisfied that all has been answered, then you are reading bad history! As Sam Wineburg writes, ‘True historical inquiry must end where it begins: with a question mark.’1 It’s not that we can’t ever make strong arguments about what happened in the past - of course we can. The heart of a historian’s expertise is in their ability to use evidence, archival and beyond, to lay out a narrative of what happened. At the same time, only a tiny sliver of the past remains for us in archives. Just think of how much you do in your daily life that’s never recorded, despite the likelihood that you have a recording device with you during all your waking hours. The exciting part about making the attempt to relate what happened in the past is that it is forever shrouded in mystery. Also, certain people and events got deliberately silenced or never got recorded due to the perception in their time, or later, that they were not worth remembering. These absences create all kinds of questions, for historical events in recent times as well as in the distant past. So, keep accumulating questions and enjoy being dissatisfied. It means you are getting a more accurate picture of what we can understand about the past.

Why is the podcast structured as daily short episodes?

I want to bring listeners into the process of how history is made. I hope others are inspired to chronicle their historical research journey like this, or in a way akin to what I’m doing on the podcast. The more people see how historians must operate within uncertainty, the more people will understand that anyone attempting to tell you what happened must justify their version of events with the elements of good argumentation. The impression that historians just immediately create refined conclusions hides a lot of what makes professional historians worthy of heightened trust. I’m able to approach these documents in the way that I do because of years of education, training and mentorship. I hope that The Historian’s Notebook inspires people to begin their journey into historical thinking, but I also hope that listeners understand that expertise takes time to achieve.

Can you put the image of each day’s document into the YouTube video of the podcast?

Unfortunately, this is a difficult thing to do because of the way that my podcast distribution program automatically uploads to YouTube. I might be able to expand the YouTube presence of The Historian’s Notebook in the future, but I need to hold off on this until I can figure out if I have enough time to take that on.

Who were Joan and Violant?

Joan is the Catalan form of the name John, and is pronounced like Johan, but with a zh sound for the j and without the h. The Latin name used for Joan in the titles of his records in the archive is Iohannis.

Joan, born in 1350, grew up as the oldest son of Pere the Ceremonious, one of the longest-ruling monarchs of the Middle Ages. The most important thing to know about Joan is that he lacked his father’s interest in conquest and politics. Joan loved music, literature, and astrology. He also loved hunting, but the luxury of elite medieval hunting complicates our idea of what this means in terms of understanding his masculinity. At the start of his reign, the Crown of Aragon was at its apex as a Mediterranean power.

](/historians-notebook-s1-episodes/images/crown-of-aragon-map.png)

This map provides a general idea of the addition of different territories into the Crown of Aragon over time Source: Wikimedia Commons

Violant is the Catalan form of the name Yolande, and both correspond to the name Violet in English. The Latin name used for Violant in the titles of her records in the archive is Iolantis.

Violant was named Yolande after her grandmother, Yolande of Flanders. Violant, born in 1365, spent most of her childhood in Paris, at the Court of her uncle, King Charles V of France. Her time there overlapped with Christine de Pizan’s. Before leaving France, Violant benefited from high culture, as her parents were fans of cutting edge musical tastes, specifically the ars nova style of Guillaume Machaut. Her mother, the sister of Charles V, provided patronage to a large range of poets and musicians. Violant had a lifelong correspondence with her uncle, the Duc de Berry.

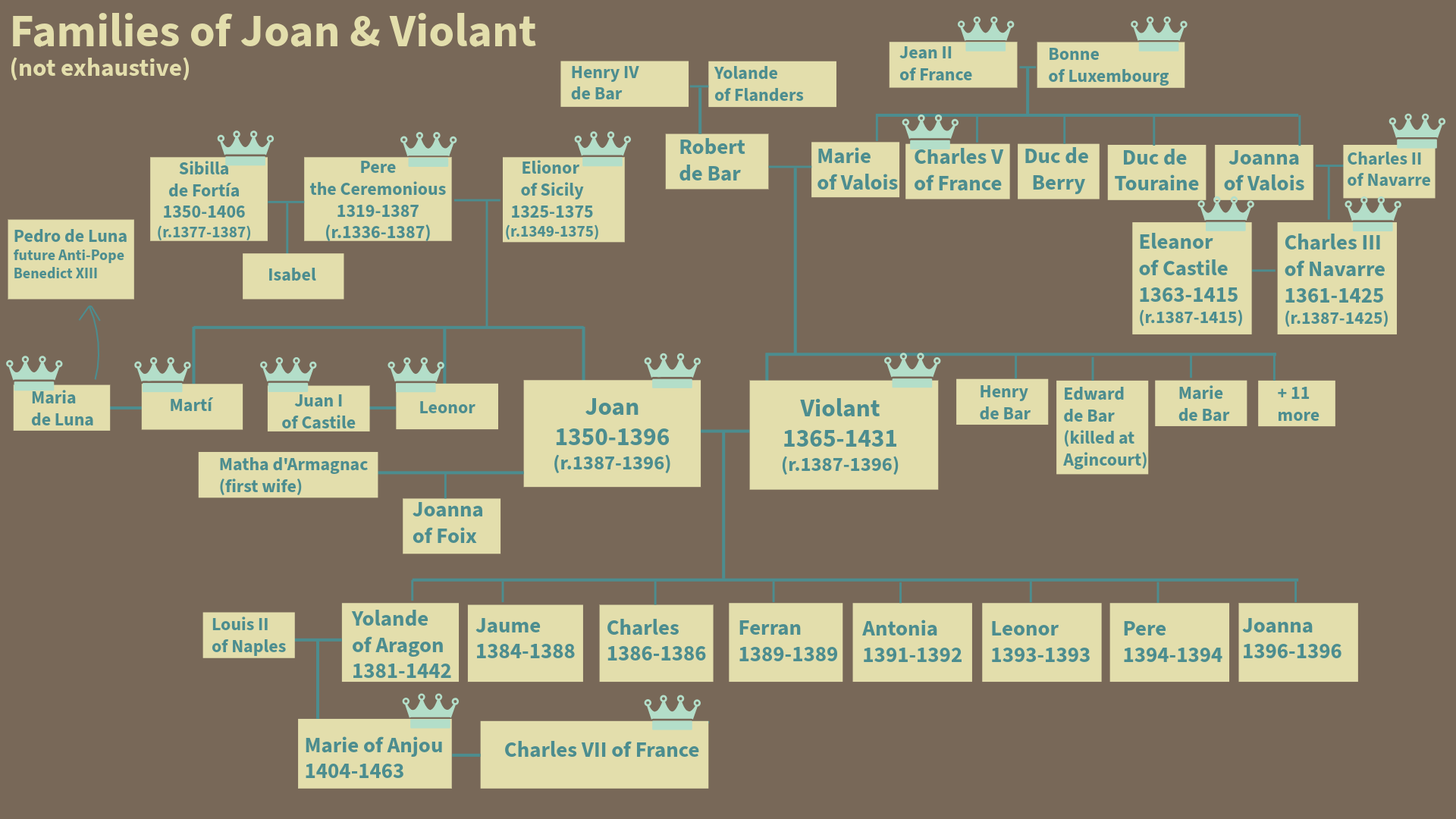

Joan married Violant in 1380. They had several children, but most died within a year of their birth. Their son, Jaume, died in 1388. However, at the time of their ascension to the throne in 1387, Jaume appeared a strong three year-old child and a secure heir. Joan died in 1396 under mysterious circumstances(!). Violant lived as a widow until 1431. The one child of theirs who survived into adulthood, Yolande of Aragon, eventually ruled as Queen of Naples. Her daughter, Marie of Anjou, grew up to marry Charles VII of France. Violant lived long enough to see her grand-daughter become queen of France.

This family tree depicts almost all of the royal family members who will be discussed during Season 1 of The Historian’s Notebook with the notable exception of King Charles VI of France.

How did you get interested in this?

I got interested in Joan and Violant after reading A Kingdom of Stargazers by Michael A. Ryan, a professor in the History Department at the University of New Mexico.2 Ryan examines how Joan, his father, and his brother, all maintained deep interests in astrological knowledge. Unlike his father and brother, though, Joan got heavily criticized for his interest in the subject. Ryan linked this to gender dynamics, identifying how Joan’s political opponents saw him as an effeminate king and Violant as too manly. This sparked my curiosity into how gender played out for elites in the Middle Ages. I think that there are many more histories out there waiting to be told of the femme kings and butch queens of the Middle Ages. Joan and Violant are just one example. At the same time, perhaps medieval gender norms were more expansive than we might think, especially for elites. The more I study Joan and Violant, the more intriguing it all becomes. Were they actually transgressive? And, if so, how?

What was the currency at the time and how much money did Joan and Violant have?

For this answer, I am going to quote from Adam Franklin-Lyons, in the Introduction to his book Shortage and Famine in the Late Medieval Crown of Aragon:

The basic silver coin was the solidus or sou (in Latin and Catalan, respectively)… Each solidus was worth 12 denarii or diners (the copper penny, again in Latin and Catalan), and the gold florin was generally worth 11 solidi. However, multiple mints in the western Mediterranean struck their own gold florin (most obviously its namesake, Florence), and the weights of those competing florins could sometimes be worth differing amounts of silver. The pound, or lliure in Catalan, worth 20 solidi, was not actually a coin and only appears in account books as a unit of measure for especially large payments or costs.3

Lledó Ruiz Domingo wrote an article in Royal Studies Journal that lays out the economics of Violant’s household during her time as the Duchess of Girona.4 She found that Violant had an annual income, as patrimony, of 400,000 sous. To get an idea of the value of that amount, the document from Episode 4 of Season 1 of The Historian’s Notebook, a payment record authorized by Violant’s treasurer, indicates that her baker got paid 356 sous for the three-month period October 1st, 1386 to December 29th, 1387 (the New Year started on December 25th).

As I continue looking at documents this season, I’ll find out more about the financial situation in the first year of their reign and I’ll edit this FAQ answer.

What is some basic information about the Archive of the Crown of Aragon?

The most abundant source to figure out more about Joan and Violant uncontestably remains the Archive of the Crown of Aragon. The archival practices in medieval Iberia differ from other regions of Western Europe due to the influence of centuries of Muslim rule. During the time that Islamic polities controlled Iberia, papermaking technology spread to the peninsula from Northern Africa, having been transferred there from the Silk Roads trade network. Especially in the region around Xàtiva, people made large quantities of paper. The abundance of paper continued into the time of Christian rule.

The material available for record-keeping met with a historical circumstance for the Crown of Aragon in particular. Jaume I, who ruled the Crown of Aragon from 1213-1276, had spent his childhood as a ward of a major legate during the papacy of Innocent III. Jaume got to witness how the papacy organized its documentation practices to bolster its authority. Once king, Jaume instituted similar practices and established a chancery. Chancery scribes began copying outgoing letters of the king as well as official proclamations, called charters. In the fourteenth century, Joan’s father, Pere the Ceremonious, as is reflected in his cognomen, developed a deep passion for what we would today call organizational behavior. Pere instituted a much more aggressive practice of documentation and funded a much larger staff for the chancery. Under Pere, the chancery scribes copied every outgoing letter from every member of the immediate royal family.

Pere also appointed a head archivist in 1346. That position has remained filled, in an uninterrupted lineage, until present day. In addition to the documents of royal families, the Archive of the Crown of Aragon also includes records from municipalities. Its scale is truly tremendous. Likewise, the recent digitization effort carried out by the Spanish government provides a level of access to this material that would boggle the minds of historians of the previous centuries, with over 33 million digitized images as of 2016. The image files for scanned material from the ACA is available through the website PARES (Portal de Archivos Españoles) run by the Spanish government for a large number of archives throughout the country.

What is some basic information about the handwriting in these documents?

The handwriting in the documents from the time period covered in Season 1, Molt Cara Companyona, is called Gothic secretarial hand. It is a form of cursive writing used, as its name implies, for business purposes. By contrast, parchment manuscripts written at the time, as valuable material objects, employed different scripts.

Two years ago, when I started looking at digitized images of pages from the registers of outgoing letters from Joan and Violant, I could barely make out letter forms. The study of historical handwritten scripts is called Paleography. Fortunately for me, one of the top experts in Paleography, Timothy Graham, teaches at the University of New Mexico. I studied paleography with Dr. Graham and also got a lot of help from Dr. Ryan. In the summer of 2024, I participated in a summer seminar on Reading Archival Latin through The Mediterranean Seminar taught by Brian A. Catlos of the University of Colorado, Boulder. I also benefitted greatly from an Iberian Paleography study group with Dr. Graham and my fellow UNM history grad student, Gavin Rogers. Dr. Graham also leads an informal Latin study group, in which I have been a member since August 2024, for transcription and translation of paleographical texts in Latin. As of December 2025, I wouldn’t say that reading late fourteenth-century Gothic secretarial hand is easy, but I can tell you that with practice it is something that can be read.

What is secondary literature?

When I use the phrase ‘secondary literature’ I am referring to the work of other historians. Secondary literature means mostly the same thing as the term ‘secondary sources.’ The term ‘literature’ helps to underscore the existence of a large body of previous work done on the topic by modern historians. This distinction helps because a work written in the distant past can qualify as a secondary source. In The Princeton Guide to Historical Research, Zachary Schrag uses the example of the Roman writer named Livy as a secondary source for the history of earlier eras of ancient Rome, prior to when Livy himself wrote.5 However, for a modern historian interested in understanding how people in Livy’s time thought about history, Livy’s work would be a primary source. The primary/secondary distinction depends on the research at hand. Schrag builds on another historian’s metaphor of sources as windows in the following quote.

Every historian, regardless of specialty, must regard sources as windows, remembering to look at the window as well as through the window. No window is wholly transparent, and without understanding the way a source frames the view and distorts the light, we cannot trust our eyes.6

This speaks to the importance of historical thinking, which means critiquing how a document was made, what it is doing, in addition to what it says.

What is the language demand for the work you are doing this season?

Joan and Violant wrote in Catalan and Latin. That is to say, the registers of their letters and their treasury records contain documents almost all in either Catalan or Latin. Violant’s letters in Catalan start pretty much immediately upon her arrival to the Crown of Aragon. Had she studied Catalan in the months prior to her arrival or did the scribes translate her French into Catalan? Within a few years Violant clearly had developed a strong fluency in Catalan, a facility that she herself wrote about within the first few years of her time as Duchess of Girona.7

In order to read the documents in the Archive of the Crown of Aragon, I had to learn some Catalan and Latin. My prior work with Castilian (Spanish) and French helped, but I spent a lot of time over the last two years working on learning languages. Latin is really difficult! If you are interested in medieval studies, start learning Latin right now.

Also, some very important secondary literature is in French. Claire Ponsich is currently the top expert on Violant de Bar and she writes in French. There is also important secondary literature in Castilian.

Lastly, if you start poking around in PARES, you will see that there are some documents from the late fourteenth century written in Aragonese. This is a language similar enough to Catalan for me to handle ok.

Are you using AI?

Yes, but with some really important caveats and warnings. First, I am using AI for help with translation. I have enough facility with Catalan and Latin to piece together how AI arrived at its translation and also (this is the most important part) how to identify potential translation errors. AI Chatbots can also help me to parse phrases in long sentences. Here is an example, using the document from Episode 1.

I also use Transkribus, a handwritten text recognition application available as a webapp. Transkribus uses AI to power its machine learning of images of handwritten text. I have been steadily working on creating a model for late fourteenth-century Gothic secretarial hand. If the Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) model works, then I will be able to get an automatic transcription of documents, making them keyword searchable. This could greatly assist in my effort to locate documents by date or by subjects of higher interest.