Season 1, Episode 6

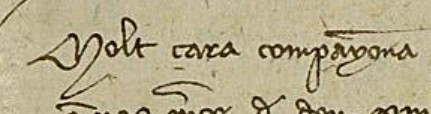

As the current king nears his last day, his son and heir transfers all the properties of his stepmother to his wife. In this document Joan initiates the change in ownership of Sibilla de Fortià’s entire portfolio to Violant de Bar.

Episode 6

](/historians-notebook-s1-episodes/images/dec-30-aca-cr-r1808-f197v-both.JPG)

ACA CR R1808 f197v Source: PARES

](/historians-notebook-s1-episodes/images/dec-30-aca-cr-r1808-f198r-both.JPG)

ACA CR R1808 f198r Source: PARES

](/historians-notebook-s1-episodes/images/dec-30-aca-cr-r1808-f198v-both.JPG)

ACA CR R1808 f198v Source: PARES

Today’s Document

- Subject: A charter granting all of Sibilla de Fortià’s properties to Violant

- Date: December 30, 1387

- Day of the Week: Sunday

- Language: Latin

- Archival Reference Number: ACA CR R1808 f197v-198v

- Link to PARES

- Place: Girona

- Authorizer: Joan

- Recipients: All of the officials in charge of the properties and collection of rents

Historical Thinking Notes

-

Sourcing: even before the death of his father, Joan created this charter for the purpose of disempowering his stepmother, the current queen; we are seeing power players making their moves; speaking of power, Joan’s power to dispossess Sibilla has gendered dimensions, much as an inverse of Sibilla’s new vulnerability now that she lacks Pere’s protection

-

Contextualization: fearing ill treatment at the hands of Pere’s children, Sibilla had fled Barcelona on the night of December 29th; there were examples of queen dowagers in the fourteenth century who suffered vengeance from newly ascending monarchs, and Núria Silleras Fernández points out that this episode with Sibilla has a parallel in the episode of Pere’s ascension to the thone in 1336, when Pere’s stepmother Elionor de Castilla fled with her sons and then fostered a rebellion;1 consider the gender dynamics involved, as Sibilla’s flight from Barcelona triggers the misogynist trope of the coniving faithless woman who betrays her husband and cannot be trusted - this trope is found in a great many cultural products of the time, such as the Arthurian legends and La Roman de la Rose

- Corroboration: in Joan’s register of letters, ACA CR R1952 f7v, he issues follow-up documentation to transfer all of Sibilla’s belongings to Violant.2

- Close-Reading: since this document is in Latin, I am limited in my ability to close read; what I can say, though, is that the length of this document and the list of officials called to action reflects the level of comprehensiveness required for such a large-scale action

What is this document doing?

- This document establishes a legal basis for the political maneuvers of the succession planned by Joan, Violant, and Martí.

- The document initiates a transmission of information to officials throughout the realm, instructing them to no longer recognize Siblla as owner of the various rents and properties.

Questions

- What was Violant doing at the time of this document’s creation? Where was she?

- How quickly could letters be delivered across distances such as that between Barcelona and Girona?

- Who was Joan’s source of information after Martí left Barcelona in pursuit of Sibilla?

- To what extent was the apparatus of the state available to Joan in the days leading up to Pere’s death?

- Who were Joan’s principle allies in Barcelona at this time? Who were his enemies?

- Did Sibilla have any power base at all in Barcelona or did she read the situation correctly that she needed to flee for her own self-preservation?

- Did the impending transition of power feel orderly? If not, how chaotic was it?

- Where were Joan and Violant’s children at this time?

- When does Joan start experiencing the symptoms of the illness that will delay his arrival to Barcelona?

Additional Notes

This document thunderously initiates the succession with dramatic action. I think that it was on December 29th or December 30th that Violant and Joan found out about Sibilla fleeing Barcelona. Violant’s letters halt from December 28th to January 6th, with the exception of a very short one on January 3rd that lists its location as Girona. My theory is that the pause in her letters is an indication of Violant’s rush to get to Barcelona.

Understanding Sibilla’s role in the succession requires knowing some of her backstory. Initially, when Pere and Sibilla made their relationship public about seven months after the death of Joan’s mother, Joan supported it. But when Pere decided to marry her, it turned into a threat, as a young son could be a pretender to the throne behind a rebellion.

The relationship between father and son further deteriorated when Pere opposed Joan’s marriage to Violant. Then, in the 1380s, the King and Queen repeatedly instigated conflicts by proxy against Violant. In one instance, Pere and Sibilla picked a fight by trying to get a high-born lady to become part of Sibilla’s household. When the lady refused, Joan and Violant protected her. In an effort to diffuse the situation, Joan went to see his father. Pere refused him entry to Barcelona and Joan waited outside in the suburb of Martorell for all of June and July 1386.3

When Pere’s imminent death became clear, Sibilla de Fortià fled to her brother’s castle, St. Martí sa Roca in Catalonia, sometime around December 22nd or maybe even as late as December 29th. Historians differ on the exact timeline. Martí, who had been at his father’s bedsie, went to that castle and waited outside. Eventually, Sibilla surrendered.

Bibliography

- Bratsch-Prince, Dawn. “The Politics of Self-Representation in the Letters of Violant de Bar (1365–1431).” Medieval Encounters 12, no. 1 (2006): 2–25.

- Ponsich, Claire. “De la parole d’apaisement au reproche. Un glissement rhétorique du conseil ou l’engagement politique d’une reine d’Aragon?” Cahiers d’études Hispaniques Medievales 31 (2008): 81–117.

- Roca, Josep M. Johan I d’Aragó. Barcelona: Institució Patxot, 1929.

- Rohr, Zita. “Lessons for My Daughter: Self-Fashioning Stateswomanship in the Late Medieval Crown of Aragon.” In Self-Fashioning and Assumptions of Identity in Medieval and Early Modern Iberia, edited by Laura Delbrugge. Brill, 2015.

- Ruiz Domingo, Lledó. El tresor de la reina: recursos i gestió econòmica de les reines consorts a la Corona d’Aragó, segles XIV-XV. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2022.

- Ruiz Domingo, Lledó. “Surrounding the Future Queen of the Crown of Aragon: Violant of Bar’s Household as Duchess of Girona (1384–1386).” Royal Studies Journal 10, no. 1 (2023): 96-135.

- Ruiz Domingo, Lledó. “Queenship, Wealth and Material Culture in Late Medieval Iberia: Sibila de Fortià’s Evolution from Royal Mistress to Dowager Queen of the Crown of Aragon (1375–1387).” Journal of Medieval History 50, no. 5 (2024): 615–36.

- Silleras Fernández, Núria. “Money Isn’t Everything: Concubinage, Class, and the Rise and Fall of Sibil.La de Fortià, Queen of Aragon (1377-87).” In Women and Wealth in Late Medieval Europe, edited by Theresa Earenfight. Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

-

Núria Silleras Fernández, “Money Isn’t Everything: Concubinage, Class, and the Rise and Fall of Sibil.La de Fortià, Queen of Aragon (1377-87),” in Women and Wealth in Late Medieval Europe, ed. Theresa Earenfight (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 67-88, at 80. ↩

-

Lledó Ruiz Domingo, “Queenship, Wealth and Material Culture in Late Medieval Iberia: Sibila de Fortià’s Evolution from Royal Mistress to Dowager Queen of the Crown of Aragon (1375–1387),” Journal of Medieval History 50, no. 5 (2024): 615–36, at 632. ↩

-

Núria Silleras Fernández, “Money Isn’t Everything: Concubinage, Class, and the Rise and Fall of Sibil.La de Fortià, Queen of Aragon (1377-87),” in Women and Wealth in Late Medieval Europe, ed. Theresa Earenfight (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 67-88, at 78-79. ↩